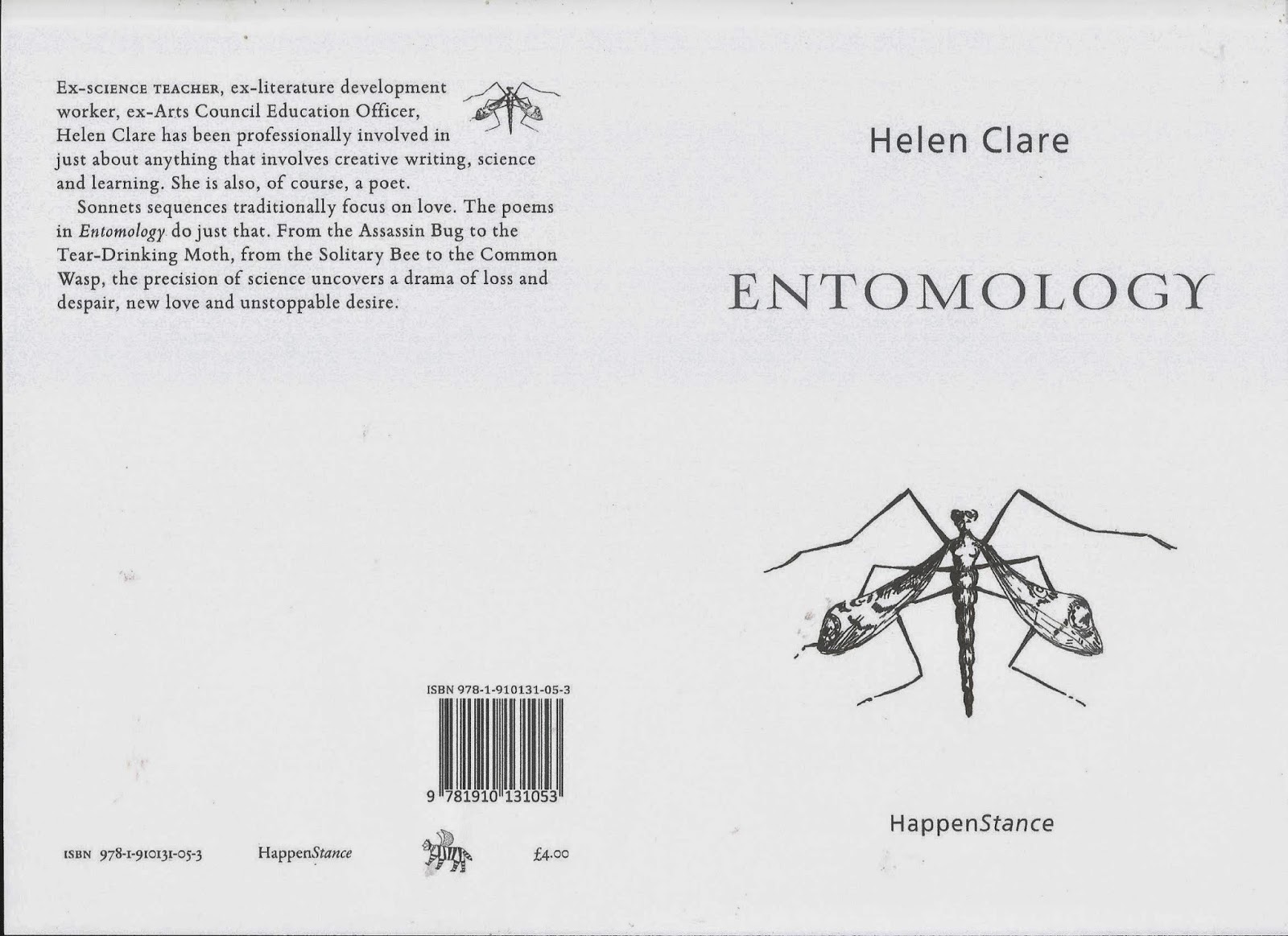

Entomology by Helen Clare

-Reviewed by Jessica Traynor–

In Entomology, Helen Clare uses a sonnet sequence on insects as a lens through which to explore love, history, broken relationships and the pleasures and dangers of courtship. In these engaging poems, the insects the poet has spent her life observing become an intriguing microcosm for humanity as a whole. Although she has a scientific background, Clare’s deep knowledge is worn lightly, informing the poems’ imaginative scope rather than becoming a didactic prop. The formal and thematic unity of the collection is hard to fault.

Clare finds a number of outlets for her undoubted creativity within the constraints of the sonnet form: in ‘Caddisly (Larvae)’ a caddisfly opens a window on her schooldays, while in poems such as ‘Greenfly’ and ‘Solitary Bee’, the poet shows us the world from the insects’ point of view, turning up some illuminating observations:

We crawl into the leavings of other lives –

empty tunnels, shells of the soft-bodied

long dead(‘Solitary Bee’).

Arguably, these poems have a more lasting impact than the more overtly personal poems, which occasionally seem to struggle a little in the transition between the insect metaphor and the exploration of the poet’s own experience.

Clare demonstrates her care for form in the many different permutations of the sonnet on display here, and there’s a real sense of her awareness of how stanza delineation affects our understanding of the poem. A slightly more experimental approach is on display in ‘Cranefly’. Though her use of white space is refreshing, this poem is consequently one of the more oblique in the pamphlet.

There is humour here too, in poems such as ‘Very Hungry Caterpillar’, in which the caterpillar writes back to Eric Carle, the author of the children’s book, to set the record straight on questions of calorie intake:

But I should mention (I have tweeted this before)

That I was never a glutton: I always

Ate my greens. Five a Day. Change 4 Life.

Live Well. We need to be on message, these days.

If I were to identify a moment when Clare risks puncturing the delicate surface tension of her own poetry, it’s when the personal declarations become a little too raw, lending the poems a slightly more earthbound feeling than those in which she allows her imagination to take flight. For example, while the content of the final lines of ‘Assassin Bug’ is effective, the attempt to fit such a bold statement into the final lines of a delicate sonnet leaves us with some rather awkward syntax:

Or why when, before our marriage, he said

He was selfish, I thought he exaggerated.

This pamphlet’s real strengths lie in the moments where the personal becomes a focal point within the broader universal. Here, the imagery is strange and striking: the cockroach’s certainty of survival in ‘German Cockroach’ is framed by an image that deftly evokes the scarab-worship of the Ancient Egyptians: ‘One day you’ll fit my carapace with crystals/ and chain me to your collar.’ This poem speaks eloquently on the pain of rejection and loss. The knife-edge between sex and death is neatly evoked in ‘Common Wasp’ where the tailored design of nature gives way to an all-consuming tidal wave of pleasure:

The waist, that carries

blood and nerve, diffusing air and gut,

is so fine that like the trillion viruses

that dance on the head of a pin, or the sting

that tapers so perfectly, it seems there is

something between something and nothing.

At the narrowest point at which two bodies bond,

tonight the angels fizz upon my tongue.

These are passionate poems by a skilled poet whose creativity blossoms within constraint. Their intricacy and intelligence augur well for the full-length collection that should surely follow soon.