I Am Here by Laila Alj (Are We Where We Are? Shop Front Theatre, Coventry, 7 June 2017)

reviewed by Stella Backhouse

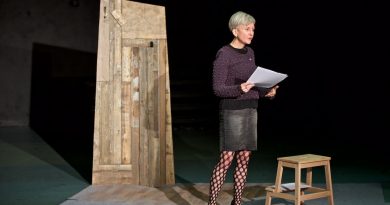

In the wake of a general election whose main outcome has been to heap yet more uncertainty on our heads, Theatre Absolute’s Are We Where We Are? series has never looked more prescient. Comprised of nine specially-commissioned works to be premièred at Shopfront Theatre Coventry during 2017 and 2018, all the contributions to this mixture of short-form performance pieces and more traditional drama have come about in response to the central provocation Are We Where We Are? I Am Here, written and related by Moroccan-born actor Laila Alj, is the second in the series.

As with Jules Orcullo, whose curtain raiser May Utang was a meditation on the lingering legacy of colonialism to personal identity in cultures around the world, I Am Here takes the audience with Alj on a journey across three continents as she searches for fulfilment in the career of her dreams. But this is more than simple travelogue. It is actually an exploration of one woman’s quest to construct a coherent self from a world not just of endless social and political upheaval over which we as individuals have almost no control, but also of other people’s prejudices.

Growing up in Casablanca, Alj viewed the perceived freedoms of America as the solution to the political, social and intellectual oppression she experienced at home. But the chance to study first in Chicago and then in New York only brought more confusion. Americans, she discovered, are not free from preconceptions of their own – one of which was that Africans are supposed to be black.

Struggling to find her niche in a culture that couldn’t slot her into its ready-made boxes, Alj headed next to London, whose ‘messy multiculturalism’ would, she hoped, offer more possibilities to achieve the life she wanted. This time, another colonial legacy – her entitlement to French citizenship courtesy of her French great-great-grandmother – allowed her to settle here. Until, that is, the events of 23 June 2016, and the still-unresolved questions around the future of UK-resident EU nationals, brought everything crashing down.

And it doesn’t end there. Alj’s reaction to Brexit:

I hope it works out but I hope it doesn’t. Should I give it it a big Fuck You? Should I try to stay?

typifies, she says, another source of chronic insecurity: the generational anxieties of herself and her fellow-millennials. Too terrified of the consequences of making decisions to ever actually make any, and too impoverished to be carefree, Alj portrays her contemporaries as a generation paralysed by inertia.

The frustrations of the individual, thwarted in their ambitions by inauspicious milieux and at the mercy of events, is at the heart of Alj’s tale. It is perhaps a measure of her desperation that she is driven to seek a solution – of sorts – in an unusual and unexpected place.

Woven into the larger narrative of Alj’s search for a place to call home is another, more intimate story: that of how she visited the shrine of Sidi Abderrahmane in Casablanca in search of a wise woman to tell her fortune. She seems slightly surprised to find herself deciding on such a remedy, but says she is “curious, and open to hearing what the woman had to say” and that she is interested to see how it feels “to put my faith in something”.

Following various spells and incantations, the climax of the consultation arrives when Alj is asked to stand over a bucket into which the wise woman throws pieces of molten lead, to see how they will fall. Her conclusion (“you’re not unlucky, but you’re not lucky either”) appears to offer scant comfort to someone in search of certainty, but Alj seems comforted by it, and wonders if it was behind the job offers she received on her return to the UK.

I Am Here could be seen as a window into rather a bleak world, but despite Alj’s many disappointments, it still points to reasons for hope. The first is that however justified Alj’s generation may be in their anger at selfish Baby Boomers and their perfect, have-it-all lives, there are still many experiences that everyone shares. Alj’s realisation that “I’m not as unique as I thought I was” is surely a rite of passage that brands us all, as we travel towards whatever trappings of adulthood we eventually manage to affect.

The second is what happened at the shrine. In attempting, however haltingly, to take responsibility and wrest back control of her destiny, Alj could be said, perhaps, to be giving birth her reborn self as she stands over her bucket. Afterwards, she faces the future with new resolve:

There is no such thing as failure, I can adapt.