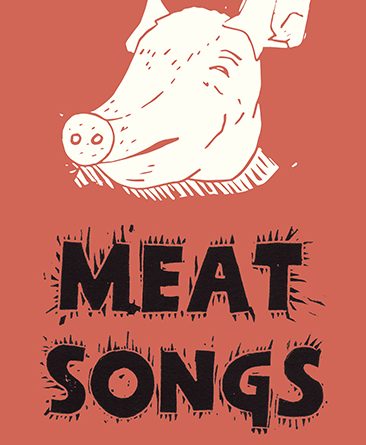

Meat Songs by Jack Nicholls

– Reviewed by David Clarke –

Jack Nicolls’ unsettling debut pamphlet Meat Songs explores our curious relationship to other animals on this planet. We invest animals with competing (but often strong) emotions: they are our companions, friends, child or partner substitutes, but also (for those who choose to eat meat) our food. They provide comfort and a respite from loneliness for some, but we also wear their skins and kill their infant offspring when we decide that they have no economic value to us. Their suffering can inspire compassion, but also provide entertainment to those with a taste for such things. They perform profitable labour for us, but are also part of our leisure economy. We manage these contradictions mostly by dividing animals into those we treat like family (cats, dogs, budgies, the odd iguana) and those we farm. Animal poems are hardly a new phenomenon, but what strikes me most about Nicholls’ work is his ability to estrange the reader from these norms, defamiliarising our perceptions.

In fourteen texts, nine of which are prose poems, Nicholls speaks in the voice of a headlouse, a severed pig’s head, a goldfish, dogs and tigers, reflecting on the place of these animals in the world that humans have made. In some of the poems, the often brutal nature of that world is conveyed through a kind of stream of consciousness, in which the thoughts of the animals in question are imperfectly transposed into human language, as if Google Translate is reading their minds:

After it all. Sucking and chewing up veggies and scum. Some of it the scum off us. And mum ripped away. All of her just a gone froth now in my mouth. A white paste just. And grey and gigantic in a hot shed. Pressing hard up to my family. Teeth knotted in our heads. Taking just the mud into myself on black days. This need to swill something. The oil of body always touching another body. (‘Severed Pig’s Head’)

Elsewhere, Nicholls incorporates insects into performance art (‘Ants March on my Torso’) in order to cunningly satirise both the potential laziness of such artistic practice and the human tendency to project our own selfish concerns onto the animal world:

For an additional fee, I can make my bodily movements more erratic – I might have a coughing fit, or roll onto my front. It is not guaranteed that the ants will reroute or perish. You will be responsible for deciding whether the ants are suffering or triumphing ingeniously.

In what is, for me, the most disturbing poem in the pamphlet, the strands of a pack full of ground mince adopt a collective voice, celebrating their intermingling. This in turn becomes a metaphor for love that stands in sharp contrast to their ultimate use as human food:

Did we ever press as close as now, did we know

one another with our skins on, do we know

what long bad night comes next? Why not love? (‘Ground Mince Sonnet’)

In its surrealism, its dark comedy, its pitch-perfect sense of style, and its exploration of the surprising possibilities of prose poetry, this pamphlet puts me in mind of Luke Kennard’s work, although Nicholls has a voice all his own. Despite drawing attention to contentious issues, there is no preaching here. Rather, the poems express a quizzical wonderment at the strangeness of things, which is more powerful in its potential to recalibrate our views on the subject than any ranting polemic.

The poems are accompanied by bold, monochrome linocuts by Mark Andrew Webber that manage to combine the apparent friendliness of illustrations for a children’s book with a sense of unease, reflecting the mood of Nicholls’ texts. A chunky bulldog is shown with drool dripping, the ground mince has little worm eyes in it, and the grumpy cat that accompanies a poem of the same name looks positively malevolent.

All in all, this is an unusual debut from Nicholls, quite unlike anything I have read of late. In a world not short of so-so and samey poems, that alone is a strong recommendation.