Vivarium by Maarja Partna, translated by Jayde Will

–Reviewed by Simon Zonenblick-

Weaving in and out of remembered places, the poems seem to inhabit dream-like landscapes and dreams, their narrator slipping in and out of time zones:

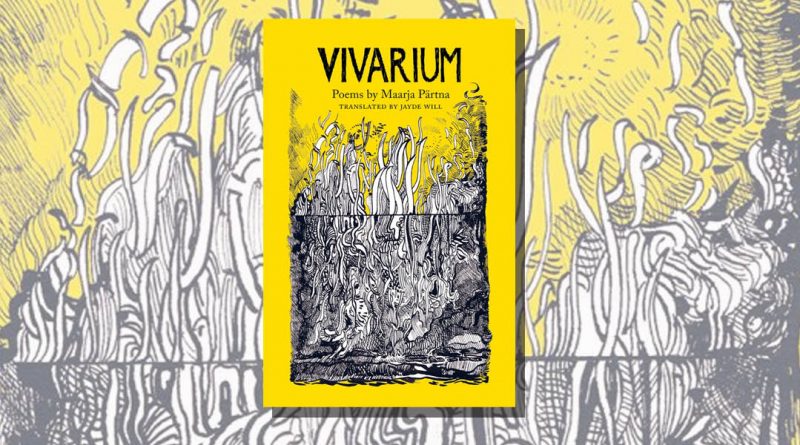

First published in Estonian in 2019, Maarja Pärtna’s Vivarium (The Emma Press) is reprinted in an English translation by Jayde Will, in a slim yellow pamphlet with a cover image by Lilli-Krõõt Repnau that gives it the appearance of some book of magic spells. The poem titles, also, lend a sense of folk-like mystery. Some are given intriguingly lyrical names like mindscape or solastalgia; most are named after parts of a house, bedroom, bathroom, attic or garden, and are mostly one-word titles – so that the well, with its connotations of mediaeval European villages, sounds like the title of a fairytale.

I sometimes visit those places

that are no longer there –

their smells, surfaces, light and shadows

Like a fragmented travelogue, the book takes us to, among other liminal locations, secret shelters, where its author observes the illegible scrawlings / of jackdaw flocks in the sky / above a scared city, to my garden / that last Soviet summer, and to that old house / by the woods in the middle of a busy harvest.

Maarja Pärtna, explains the blurb, ‘explores the uneasy co-existence of the past and present, on a national and global scale, and looks to the future with anxiety as well as hope’ and ‘reflects on the effects of Soviet rule on Estonian society.’ Perhaps this is most acutely conjured in the poem communal flat, with its extremely tiny rooms / in a country where an immense history / forced strangers to live in close quarters.

The blurb goes on to describe how Vivarium comments on humanity’s treatment of natural habitats:

a damp future rises up from the stone floor

past my ankles ever higher, runs over

the top of my boots.

guess which of these it is –

a woman’s water breaking

or the beginning of the flood?

The emergence of nature filling human voids is also touched upon. In the poem tourist visa, where all that was left / of the two green military barracks / were some piles of bricks / the outlines of rooms, corners and thresholds / still detectable in the grass / that had grown tall

The metaphor develops, as even the asphalt roads/ had surrendered to the onslaught of grass, and the blackcurrants, gooseberries and white translucent apple trees / growing through frameless windows / through non-existent walls / right into the kitchen and living room do not appear to have remembered much / at all from their life as pruned garden plants.

The lack of punctuation and capitalization adds to the sense of a sanding down of linear structures, as suggested by the piles of bricks and ‘non-existent walls.’ Like the collapsed ceilings and ruined cities peppering this pamphlet with eerie omens, walls appear ominously. Their oppressive qualities are suggested by poems like bird cage (whose two-word format, as opposed to ‘birdcage’ forces us to confront the significance of caging life) as something we have always built. / walls to keep something in / walls to keep something out. The glass house imagery of the title poem is perhaps the perfect political metaphor given the background of the poems, and a stunning way of suggesting the fragility, and hidden divisions, between lives. Indeed, its narrator speaks of its glass enclosure in terms of a transparent wall.

The power of memory bleeds through the poetry, with its remembered homes where I used to belong, its mirror turning into a peephole / which shows an entirely different world, its photographs where I / captured you and made you become / unchangeable, defined

Revisiting a childhood or past, the poet finds herself inhabiting an empty house where a door / begins to take shape around me / one that was impossible / for me to go through before. Standing on a threshold that doesn’t exist / in a house whose very foundations / have been carried back to the fields / stone by stone, they tell us how most probably I never / really left this place.

There is something reminiscent of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, in the way the poet takes us on her surreal journey, where nothing is exactly / what it appears to be – the walls hide / hidden doors and the doors hidden walls. We are taken over unstable bridges:

a broken handrail

a crumbling boat dock over a chasm

rusty screws unscrewing themselves

from the rotten planks

and join the poet at the beginning of a journey towards / the future and the unknown.

Images of old homes or the landscapes of yesteryear are seen through a prism of change or dereliction – be it the old spiderwebs, shriveled-up bat mummies of attic, the exhausted steps of staircases in communal flat, or when, in contrast to the earlier photograph recalled in Portrait, the poem Stairs tells how:

things should stay unchanged

but still – the potatoes have sprouted white bristling hair

next to the wall a crumpled mouse skeleton

shaped like a crescent moon. something always waxes

something always wanes.

In the freeze frames of photographs, we can retain an image unchanged by the passages of time, or bend a memory to how we want to see it – two edges slice your body in half – but the real, physical world alters, shattering the sanctuary of memory:

the river I wanted to wade in

a second time has dried up

and no amount of self-knowledge

will bring it flowing back to that old riverbed.

As in the dried up riverbed scene above, the imagery of Vivarium often focuses on environmental decay:

next summer its not a flood

but a drought. the news says in brief

“this could be the change. ”

Against a backdrop of psychological and environmental unease, there is definitely a subtly expressed desire to escape in Vivarium – but it is sometimes framed within the claustrophobia of apparent acceptance – in the title poem, the incarcerated narrator insists this house of glass is not my home, but confesses I don’t want to leave, I don’t need / a new home in cold, dark space

The capitalized I in the poem above – one of the only times this occurs except at the onset of a sentence – is notable – as if illustrative of a newly evolving sense of self. The poet’s gaze throughout seems to be uneasily balanced between the world around them and their own internal ‘mindscape’. We have a sense of being anchored, or rooted, to the past, whether this be positive or negative, and whether it relate to human memory or the foundations of the natural world:

is it even possible

to contain relentless thoughts that pierce the skull

like rusty swords that cut the earth

in spring when fields are ploughed

or birch roots that burrow ever deeper

through the centuries

through the strongest doors of faith.