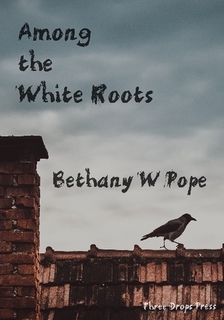

Among the White Roots by Bethany W Pope

– Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey –

The first impression of this latest chapbook, Among the White Roots, from multi-award-winning poet and author, Bethany W Pope, is a visual one. The cover is striking, with intimations of foreboding – a crow on a red brick wall, cloudy sky in the background. The poems for the most part are very short, but with each line stretched right across the page. This creates an effect of surface concentration, and below, a lot left unsaid.

We are brought into an underworld filled with birds of ill omen, such as magpies, rooks and crows, and a medieval atmosphere of castles, gargoyles, cobblestones and a horn-carved door. The entrance to this underworld awaits, the blurb tells us, ‘in Swindon.’

Fear and apprehensiveness are vividly conjured: ‘He showed me small, / Iridescent gemstones (blue and red). I / Zoned out when he strung them around my neck.’ (‘Into the Dark’). Ultimately, however, fear reverses into powerful rage: ‘‘Please let me speak.’ I cut him off. Awful / Rage set fire to my heart’ (‘Edged Words’). These poems are distilled to a point of intensity.

Pope is an academic with a PhD under her belt, and her work demonstrates a sophisticated use of form. Here we find double acrostic sonnets and deconstructed acrostic sestinas, as well as an acrostic specular. On top of this, she uses language that is heightened to a gothic level. But she never loses control. On the contrary: ‘when the sweat had cooled on my skin, I saw you clearly for the first time. Free of the intoxicating illusory mask that desire projects onto the object of love, I saw your hollow eyes (bone sockets wound through with the white roots of lilies) and I knew, at last, what my desire meant.’

In most cases, the titles here are arresting: The Room of Past Brides, or Before the Man-God Dragged Him to the City, or The Wives Argue for Order, or Between Four Burnt Walls and a Skin-Patched Roof. The tone is formal and assertive: ‘Swindon is a morbid little town, with / Keen appetites.’ (Town Centre). Pope’s use of aphorisms adds to this sense of authority: ‘Death has always craved the young’; ‘Life comes from blood, not stones’ (Rook). The cumulative effect of words such as ‘sweet’, ‘death’, ‘earth’, ‘dirt’, ‘filth’, soil’, and ‘The Corvidae Chorus’ create a chillingly morbid atmosphere in which Death is personified: ‘‘Remember you tried, and failed, to draw / Escapees from my pit,’ Death said. ‘Remember that I tried to help you climb’’ (The Grave Refunds Silence). The birds, too, speak. In ‘A Fungal Forest’, ‘‘You / vain little creature,’ one age-white gore crow / Exclaimed, ‘craving more than you’re owed by life. / Remember, my dear, the teachings of fear.’’

In a section evoking Bluebeard, titled My Lover’s House Has Many Rooms, Pope casts her net more widely, and exotic words begin to appear: ‘hadj’ (an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca) and ‘veldt’ (which evokes the African savannah), a word repeated in later poems. This is disconcerting initially, especially when the first ‘veldt’ poem also includes the word ‘portcullis’, bringing us back to medieval fortifications. Perhaps a separate section for the more exotic references might have been more effective.

Pope has particular strengths in evoking atmosphere, and in her use of images to articulate the inarticulate. The language is earthy with fungi and excrement, and whether the settings are outdoors or inside, they are image-rich, turbulent and compellingly grotesque. Using her own particularised forms, she finds a way to deal with difficult material that must be addressed. Thought-provoking, dense with suggestion, her best poems here, in my view, are her sonnets, which lean towards myth, adding her own layers to universal stories:

In the candle light, rare meat glistened. Fruits

That never sprang from mortal soil (filled to

Splitting with juice) glittered in the bowl. ‘You

Ought to try these pomegranates.’ Laughing

(Fire gleamed on his teeth) he brought a spoon heaped with

Many-hued seeds to my trembling lips. ‘That,

Young lady, is what Death is like.’(The Food of the Dead is Round and Red)

Though the use of exciting form and language, scenarios rich with mystery and menace, and a personalised mythology, Pope has achieved a form of transcendence. Among the White Roots is a timely and impressive achievement.