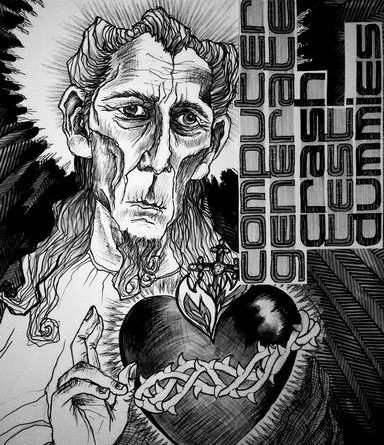

Computer Generated Crash Test Dummies by Graham Clifford

– Reviewed by Jessica Traynor –

Graham Clifford’s pamphlet, Computer Generated Crash Test Dummies, looks at traumatic life events from a number of different angles, forensically deconstructing them in a series of muscular poems. The pamphlet’s title poem is among its most striking, dispassionately observing the many permutations of an accident, watching the waltz of two crash test dummies being propelled, again and again, through a car window. The poet, in his role of observer, assesses the benefits of such an exercise:

Every permutation of falling is being logged.

Soon there will be nothing we don’t know

about how to be broken.

The poem’s emotional impact comes from the poet’s recognition of the human form of these dummies, the implications of their ways of landing. There is a pathos here that avoids easy sentimentality:

Now we are dropping couples

to see if they end intertwined:

one rests on another’s head;

it might be that their legs knot

or, side by side, a hand is accidentally on another’s.

The flip-side to this detached mode of observation is explored in ‘Pro Forma’, which questions the agenda behind attempts to catalogue disaster in medical records. The weariness of the tone here is cut through with flashes of anger, as the grotesque nature of the medical form’s requests is vividly rendered for us:

The limbless, parboiled and lightly electrocuted

must vomit, gibber and proceed dented,

ranked between these two possibilities.

By the poem’s end, the poet has made a plea that seems almost to echo poetry’s own drive to eschew neatness and certitude for the more fertile realm of suggestion, avoiding “the poisonous security of loose ends tied”.

These poems mine the darker side of life, but do so with a genuine and engaging curiosity. Clifford presents an apocalyptic vision that is all the more discomfiting for the tone of weary normality that imbues the poet’s observations. Imagistic poems such as ‘Blood’ and ‘That No Good Will Come of it’ are expansive, almost hallucinogenic visions. The latter imagines a gender fluid Janus-style god whose cycle of self-destruction creates humanity as a sad bi-product:

she stares boss-eyed at real people

doing real good

and reaches inside himself to get a hold

on her own guts, pulling them out

and out, a long comedy routine

of blood and intestines and when he stops

is where we are.”

‘Blood’ evokes a similarly nightmarish vision of contemporary life, where extreme violence has become mundane; barely worth commenting upon: “We walked through crops doing well on blood./ I drank cups of the stuff./ This became the new normal and no one seemed to mind.” These poems are unremittingly bleak, and yet the vividness of the poet’s vision lifts them above mere nihilism.

The pamphlet has its moments of humour, including ‘The Rules’ which takes an acerbic swipe at the limitations placed on poets by questions of what constitutes good taste or proper poetic subject matter:

Don’t discuss the poor,

definitely not poor children

with Coke for blood, thin hair, cartoon thoughts

giddy with particulates: that’s not fair of me.

There’s also an affecting tenderness to be found in poems such as ‘Elegy’ and ‘Ghost’, and this tempers the pamphlet’s blacker moods with an understated wistfulness.

These poems are conversational in tone and would clearly lend themselves well to performance. There is a risk at times that chatty digression may undermine the clarity of the poems’ central imagery, but for the most part, the visceral nature of the work wins out, making this a refreshingly direct pamphlet, full of startling visions.