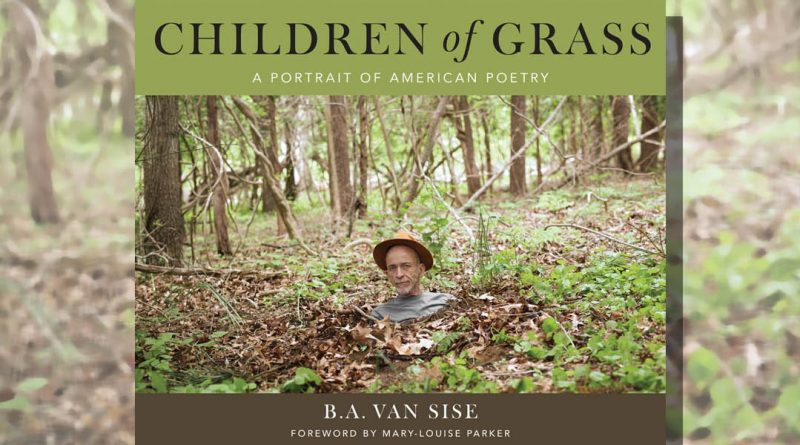

Children of Grass Edited by B A Van Sise

-Reviewed by Simon Zonenblick-

The beautifully presented Children of Grass is described in its foreword by actor Mary-Louise Parker as “a revelatory testament to the legacy left by Walt Whitman.” The spirit of that great American poet is invoked in 156 pages of poetry and photography to coincide with the bicentenary of his birth. Edited by award-winning photographer and Whitman descendent, B.A. Van Sise, whose images accompany poems by contemporary US writers on facing pages.

“These pairings speak to each other without polluting the mystery of the other or revoking the license to interpret that poetry gives us” writes Mary-Louise Parker. All the same, it is the assorted images that bring the book to life. While the sequencing of the poetry lacks a concrete theme, the enticing, sometimes spiritual, sensual or subversive images – such as characters in dressing rooms, on sidewalks, or staring into the Heavens, whose power lies in sideways glances, eyes cocked to the sky, the deafening silence of a typewriter abandoned in a room, a man’s face in the mirror as if upon a sea of wavy lines – play out like a montage.

“I like to touch your tattoos in complete / darkness, when I can’t see them,” begins Kim Addonizio’s ‘First Poem For You’ – opposite the black-and-white image of a woman holding hands with a scarecrow decked in long black coat and reptilian hand. The narrator is sure of where they are, and knows

by heart the neat

lines of lightening pulsing just above

your nipple, can find, as if by instinct, the blue

swirls of water on your shoulder here a serpent

twists, facing a dragon.

The poem evokes suggestions of permanence and deep, if liminal, connections between lives – a sense of reassuring familiarity. This is also evident in the brilliant ‘Becoming a Redwood’, by Dana Gioia:

Stand in a field long enough, and the sounds

start up again. The crickets and the invisible

toad who claims that change is possible,And all the other life too small to name.

First one, then another, until innumerable

they merge into the single voice of a summer hill.

The poet is “paralyzed by the mystery of how a stone / can bear to be a stone, the pain / the grass endures breaking through the earth’s crust” and yet feels that a human being is “part of the moonlight as the moonlight falls / Part of the grass that answers the wind.”

In ‘Escape from the Old Country’ by Adrienne Su, the land occupies the person, while Dunya Mikhail dreams:

I fell into a hole

and when I woke

I found a feather.

If only I’d put it under my pillow

before going to sleep:

I’d have dreamt I was a dove

and wouldn’t have fallen.

Other poems imagine bizarre scenarios, such as Jeffrey McDaniel’s ‘The Quiet World’, where:

In an effort to get people to look

into each other’s eyesmore,

and also to appease the mutes,

the government has decided

to allot each person exactly one hundred

and sixty-seven words per day.

The poem weaves through various surreal scenes, before culminating in a phone call from the poet to his long distance lover:

When she doesn’t respond,

I now she’s used up all her words,

so I slowly whisper I love you

thirty-two and a third times.

There are many poems I don’t really understand, with cultural references I don’t follow, or witty punchline-like endings, such as:

Bought a bag of frozen peas to numb my husband’s sore testicles after his vasectomy.

That night I cooked pea soup.(from ‘Reduced Sentences’, by Beth Ann Fennelly)

or

I love my son so much

I no longer call him my daughter(‘On the Rocks’, by Leslie Anne Mcilroy)

but it’s the beguiling photographs that hold the book together and create a compelling narrative.