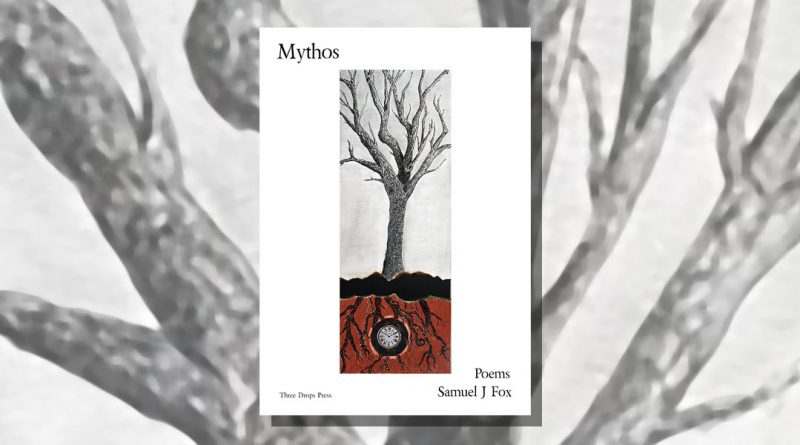

Mythos by Samuel J Fox

-Reviewed by Deirdre Hines-

Now and then I come across a pamphlet of poems which gives me pause, causing me to re-evaluate previously held certainties akin to knowledge. The knowledges that pervade Samuel J Fox’s Mythos, published by Three Drops Press, are re-writings of mythological certainties. But what are those mythological certainties that underpin the lives of most of us living in the West? If myth is the means through which man has told tales to make sense of the world we are living in, then it is a crucial ingredient of all cults, including such historical religions as Judaism and Christianity, although the role of myth in those religions is diametrically different from the so-called ‘natural’ religions. As a literary genre myth is present in Holy Scripture, especially in the Old Testament. Samuel J Fox subverts those tales and certainties in a pamphlet of twenty-one poems that are shaped for the most part in clusters of three poems , echoing the Trinity. The opening poem of each of these three poem sub-sections is titled ‘Mythology’, the next is a Self Portrait of some description, and the third poem is a twist on the epistolary that sends a nude to an iconic figure in Judeo Christianity. This is clever, particularly as myth is a literary device in Christianity, within which when speaking about God, a sign or symbol plays the same role as abstract language in metaphysics, and in which some commentators have said that the relationships between God and man are the subjects of dramatic staging. These poems are dramatic re-enactments that restage our relationships to the myths of sexuality and belief.

In the opening poem titled ‘Mythology’, the traditional binaries of light and dark are originally addressed by the poet in the first two lines:

When I walk into the night

I contuse against it…

In many ways, this pamphlet is a charting of the walk into the night of this temporal life. He was born empty of everything but light, he tells us in the second verse. Language and his first word ‘triceratops’ is addressed in the third verse, or more particularly the desire of language to want. Love finds its metaphor in the ocean in the fourth verse, particularly lost loves the poet cannot accept are dead. In the sixth, the tree on which Jesus was crucified makes its appearance in a tree of sand the poet has harvested ‘on a beach made from splinters/of wood and bone.’ The last line of that verse runs into the next and in the gap between the line ‘Tell me we aren’t God / relearning Its name’, there is space for new meanings. God is gender neutral. This allows less surprise for the range of partners the poet kisses in the seventh verse: ‘When I kiss/him or her or they’.

The poet reflects light, and it seems to be the light of love and relationship that he is most concerned with, but this is no solipsistic treatment of that most overplayed of tropes. It is much, much more than that. ‘Self Portrait in Defenestration’ sees the poet falling into the ‘heaven of Earth’s heart’, and is probably the weakest of all the Self Portraits. The block text of ‘Sending a Nude to the Wrong Saint on Accident’ uses the ampersand as a counter to contemporary symbols of the twentieth century: ‘All Calvin Klein cotton & bicep’. Indeed ampersands are a hallmark of all his Sending poems. This poem celebrates sexuality in some remembered moments of desire that is made all the more poignant by lines like these:

Tell me you’d forgive me if I hogged the covers.

Tell me you’d forgive me if I didn’t come at all.

Anaphora is a favoured device. In the third ‘Mythology’ poem, he begins each of the first three verses with ‘The first time…’ and closes with ‘the last time’ bringing both the poem and relationship to a conclusion. The lost lover is mythologised, but what makes it arresting and unusual is that the lover is made eternal through the prosaic and then eternal again by what the prosaic allows the poet to become. Kissing allows him to beome a lotus flower, but the lover is a colony of aphids. Sexting transforms him into an icicle ‘hanging onto a handrail in Russia’ that melts when the lover replies, but the danger in the lover’s replies is that it damages the poet. In ‘Sending a Nude to Saint Peter at the Gates of Heaven’ the poet is waiting for the apocalypse, without the capital. He prays that she will take him in her mouth, ‘that the Angel/of Death has strong head-game’. It is this mixture of incompatible extremes, of the shameful and the holy, the fleshly and the spiritual that surrounds myth with an atmosphere of mystery, and gives it a meaning which has always inspired the artist. Samuel J Fox charts pansexuality brilliantly in the seventh ‘Mythology’ poem. However, the curious about-turn in the second verse is troubling.

In some future distance, the love of my life

waits fiddling her thumbs or folding

his hands around a pomegranate. The first sin

was not disobedience, but mercy:

for Eve so loved the world she granted Adam

equality in the knowledge of suffering.

For millennia, woman has been blamed for man’s failings in the mythology of the Fall. I found this treatment of Eve too reminiscent of that blame culture, all the more surprising as Fox is espousing new radicalisms in sexual partnerings. Nevertheless, Fox has written an illuminating sequence that shines light on all our meanings of the real and unreal. One to watch.