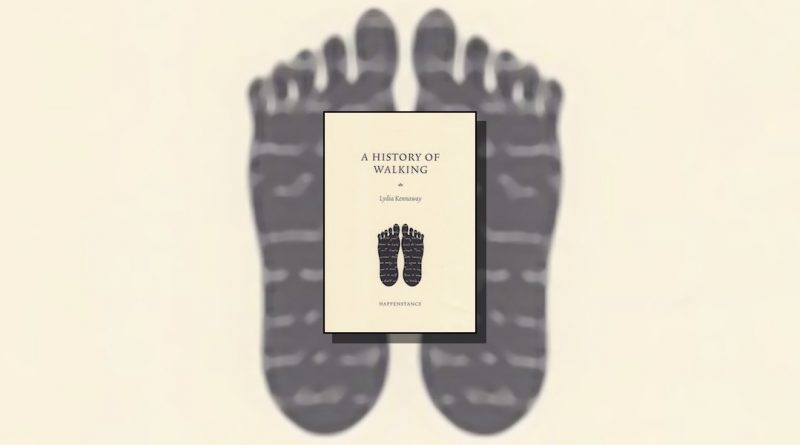

A History of Walking by Lydia Kennaway

-Reviewed by Phoebe Walker-

In this assured debut pamphlet, Lydia Kennaway explores the mass of branching physical and emotional pathways that flex, extend and dissolve around us, carefully mapping out a handful of selected journeys with warmth and skill.

It’s (literally) baby steps to begin with In ‘Sumo’, a toddler “stands, toes the mark, crouches”. For her,

I want is the small, fierce

Engine of mobility.

That first footstep is the quiet key to a collection—a ‘history’—which encompasses the Yorkshire Dales, a fairy tale woodland, the Democratic Republic of Congo and the moon, as well as the smaller spaces of the bedroom, the local park, and the street at night. The distance travelled might be the length of a carpet, or the drop from bed to floor, or the breadth of four countries. It can be a gentle arm-in-arm promenade, or a matter of life and death, “a cruel calculation of distance, fuel/ and energy burned” (‘Walking for Water’).

In ‘The Flâneur or The Observer Observed’, the poet dissects a favourite figure in literary modernism, the city wanderer who “botanises faces in the crowd”, leisured smirk implicit as he clocks a woman who:

If she’s strolling on her own—

if she’s clearly all alone—

she’s a girl who walks the streets and such a pity

Kennaway’s consistently smart work with form and rhythm helps to create a sensation of each poem being crisply differentiated from its companions; each turn of the page opening onto a very different map. In ‘The Flâneur’, the effect is darkly playful; elsewhere, it can be much starker. In ‘Advice to Women Walking After Dark’, the lines are truncated; it feels as if they are being whispered tensely from the corner of a mouth, by someone walking on the pavements’ extreme edge, the final instruction tapering into a single, ominous word:

Don’t be afraid

to use your nails: nails

harbouring blood or

other trace material

will help DNA

analysis

later

There’s an echo of the latent violence of this taut structure in a later poem ‘Las Locas’. The title refers to the movement of women in Argentina who advocated tirelessly for the truth behind the disappearance of their children during the country’s military dictatorship of the 70s and 80s. These women are writing “history with our feet”; they “walk on the Plaza in circles./ Week after week, year after year.” The footsteps here feel less about progress than pilgrimage; this is a vigil. It also serves as a division of metre, and of pain—in the poem’s brief lines and narrow structure, the long, unbearable vista of grief is paced out, separated into the manageable unit of a single step.

We wear white headscarves.

Mine is embroidered

with ‘MARIA’. See?

I’m struck by the generosity of Kennaway’s scope: the different footsteps she’s able, gracefully, to inhabit, the tone and feeling she channels in each stride. From the quiet rage of ‘Inuit Anger Walk’, where the speaker is a “a furnace in the snow”, to the semi-dazed sleepwalker, drawing a circle with a fingertip and telling their partner “I will never leave you, never.”

The controlled pathos of ‘Forgetting How’ is quietly striking. An older woman addresses us, ruefully, from the floor where she has fallen, “tripping over my own feet. Oh dear.” Timestamps from the digital clock—01:17; 01:42; 02:05 (“My bladder’s full”) structure the progress of thought with “their little acrobatic flips”, as reminisces—“I could stride up Hampton Hill without pausing for breath” give way to possible explanations: “That’s what I’ll tell them—I must have dropped off—” until, at 07:17, the poem fades out with birdsong, as the day breaks.

This collection triumphantly rescues the concept of the ‘journey’ from its hackneyed contemporary connotations. Kennaway’s versions are sharp, agile and sensitive in all the right places. These feet never plod, they fly.

Thank you, Phoebe, for such a beautifully-written review, and for the close attention you’ve clearly given to my poems.