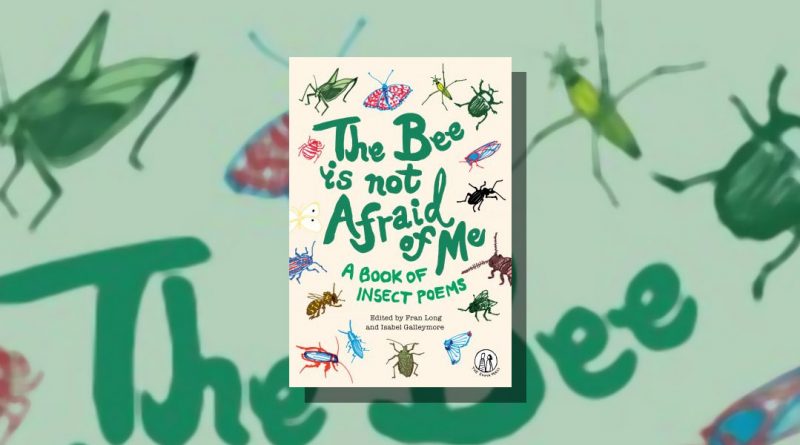

The Bee is Not Afraid of Me, A Book of Insect Poems edited by Fran Long and Isabel Galleymore

-Reviewed by Deirdre Hines-

The tradition of insect poetry has some illustrious examples; John Donne’s ‘The Flea’ written in 1633, being the most well-known. However, it is the poetry we intersect with as a child which resonates the longest. I received a copy of William Roscoe’s The Butterfly’s Ball and The Grasshopper’s Feast with nature notes by Richard Fritter and beautifully illustrated throughout by Alan Aldridge as a birthday gift from my godmother. It opened up another world beneath my feet. The Bee is not Afraid of Me is a cornucopia of forty-six poems and accompanying black and white illustrations, interesting facts with web addresses, project ideas for the enterprising parent or teacher, and an interview with a working entomologist which includes advice on how to approach a career in entomology. Inspiration takes many forms as all poets know. This book had its genesis from Fran Long’s former role as Project Insect Education Officer on the Oxford University Museum of Natural History’s Heritage Lottery Funded HOPE for the Future Project, and from the award winning poet Isabel Galleymore’s abiding passion for ecology and our human place within it. Poetry projects that arise from lofty intentions rarely realise themselves as well as this little gem of a book has. I absolutely loved it, and have no doubt it will open up the eyes and ears of children for generations to come.

The book opens with Myles Mcleod’s poem ‘Questions for an entomologist’, using questions in delightful wordplay that even brought a smile to this rather jaded ear. My favourite was

Do fleas flee like flies fly?

Do butterflies like butter?

Do horseflies fly horses?

Do bumblebees have bums?..

Celia Berrell’s ‘True bugs are suckers’ jaunty rhythm explains what I had never understood until now:

A true bug’s an insect,

but insects aren’t bugs

if they eat by chomp-chomp

instead of glug-glug

Anyone who has read poetry to children knows how often small hands creep into school satchels to nibble on something hidden there. Kate O’ Neil’s poem ‘Café Six’ is sure to be a hit with these munchers. Her café offers ‘fleas flambé’, ‘mosquito mousse’, ‘caterpillar curry’ as some of the more alliterative of dishes.

Of the poems written in the voice of an insect, Elli Woollard’s ‘Song of the Dung Beetle’ will garner not only a lot of chuckles if not guffaws at the implied colloqualism for excrement after “But I live in a pile, a big steaming pile, a HUGE steaming pile of….”

We learn there are three different types of dung beetle: rollers, tunnellers and dwellers, and that each is named for the way they use the poo they find. Susan Byrne’s ‘Our Planet’ follows this little fact box, and in it we learn how dependant we are on the small dung beetle. Poets have used natural imagery to discover important relations between the image and human experience. What is new in poetry are the poems inspired by deep ecology – the philosophy based on the belief that humans must radically change their relationship to nature. In a sense all of the poems in this collection reconnect the reader with the wild, bear witness to our insect brethren, and envision a place for the humble insect in children’s parlance. One poem in particular calls for a resistance against the way we have been conditioned to behave when met with what too many deem to be pests. Gabrielle Turner’s ‘A pest’s request’ could be read as a plea against intolerance of difference per se.

You call us creep crawlies

and you tell me I’m a pest,

but just like you, I’m living too

and I’m only trying my best.

No poetry collection would be complete without at least one acrostic poem. I do not know of any classroom that hasn’t an example pinned on the wall. They are often the first point of entry into poetry for children, and Nina Hoole’s ‘Dazzling Dragonflies’ is an excellent example of the genre. I was particularly impressed with: ‘Lace-veined wings fingerprint each species scientifically’. Jane Mackenzie’s ‘The Mayfly’ is a haiku which adheres strictly to the 5-7-5 syllabic count, but which relies on its title for seasonal reference. For those budding entomologists without recourse to computers or who do not have access to Wildlife Trusts, Ros Woolner’s poem ‘Pond Dipping’ charts a course. Its four lined verses move from iambic to tetrameter in a gently swaying motion, with an abcb rhyme scheme, lulling the reader into grabbing one of the below:

You don’t need much for pond dipping:

an ice cream tub or plastic tray,

and a net ot sieve to catch things in.

Got them? Good. Let’s go today!

I cannot think of any forgotten insect in these forty-six poems: butterflies (cabbage whites and fritillaries) moths, mayflies, termites, beetles, cockroaches, ants, honeybees, pond skaters, marmalade hoverflies, crickets, ladybirds, shield bugs all abound. Two poems have the Latin names of the genus as their chosen title: Pyrophorus Noctilus (Snapjack click beetle or Headlight beetle) and Episurphus Balteastus (or a case of mistaken identity), of which the latter has a lovely modernist twist in its take on the poetic couplet. I am still curious as to why it didn’t end with a full stop, but perhaps one of my younger co-readers will solve that particular mystery. The most arresting simile in the whole book comes from Robert Ensor’s ‘Aerial Gymnast in the Clothes of a Clown’ a paean to the honeybee. In line nine he says ‘yet you’re fragile as a child in the jaws of a hyena’. Elizabeth F. Hill’s ‘Name-calling’ is a fitting poem on which to end this review, reminding us that somewhere in our recent past, insects were thought important enough to name collectively; ‘bike of wasps’, ‘loveliness of ladybirds’. Long may they remain to flutter in kaleidoscopes of butterflies. And now to find a sieve to sit beside my local pond with. Published by Emma Press.