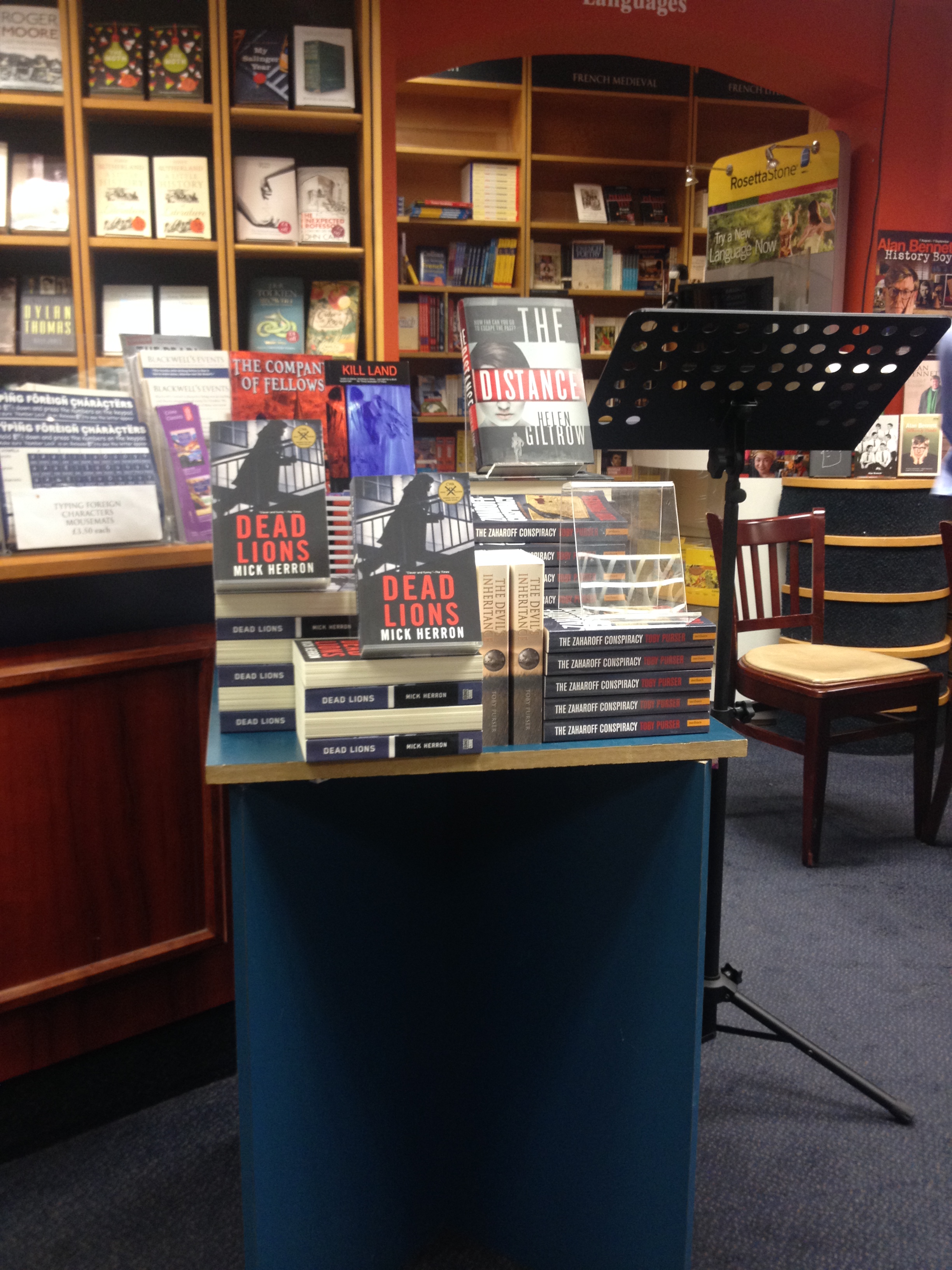

Crime Writer’s panel discussion with Mick Herron, Toby Purser, Helen Giltrow and Dan Holloway @ Blackwell’s

-Reviewed by Claire Trévien–

Crime Writer’s panel discussion at Blackwell’s Oxford Fiction Week 9/9/2014

Small confession to make: other than a period around the ages of 13 to 14 in which I was obsessed with all things Mary Higgins Clarke (translated into French of course, which made names like Megan feel spectacularly cool), I’ve not been much of a reader of noir. Of the four panellists at last night’s Blackwell’s Crime Writer’s discussion, I was only familiar with Dan Holloway’s writing. Rather un-usefully it was his poetry rather than prose that I was familiar with (with the exception of Evie and Guy of course, his novel written only in numbers).

All this is to explain that I went to the panel with plenty of curiosity but little knowledge for the genre, and left with a rather more expanded view of what crime writing could encompass and an eagerness to explore both the kinds of novels that play within the restrictions of the genre and inspired to apply some of the thoughts generated during the discussion to my own writing. Not bad for a one hour and a half discussion really.

The panel, comprising Mick Herron, Dan Holloway, Helen Giltrow and Toby Purser, was held at Oxford’s Blackwell’s to an intimate but enthusiastic audience of 30 or so friends and fans. While publicity material suggested that the talk would centre on ‘the City of Oxford as a perfect setting for the genre’, the writers discarded this for a more focused exploration of freedom, particularly the freedom of their characters. Each writer was given a turn at the pulpit to discuss the topic and read a short extract, followed by a plenary.

Toby Purser, who had suggested this new theme, discussed in particular the difficulty of writing historical fiction when you have a PhD in History. His academic side deals in fact, but his writer side needs to push against facts. His novel covers two distinct time periods: 1914 and c.1760-1834, and perhaps surprisingly, he admitted later in the panel discussions that he felt freer when writing the 18th century sections as it meant dealing with a more remote past. The general conclusion to his section was that facts are always open to interpretation and that his novel, The Zaharoff Conspiracy explored that very topic through the use of new information from the past that could put into question the present of a character.

Helen Giltrow started off with a very engaging reading of the start of The Distance. Whereas Purser writes crime fiction set in the past, Giltrow writes in the near future, so faces very different challenges. To Giltrow, freedom involves the need to create restrictions, and giving her characters ‘restrictions, often without realizing it’. In The Distance, Giltrow exploits the first person narrative to seed the idea that her narrator is not infallible in judgement or necessarily reliable. Giltrow also interpreted freedom as her own freedom to write a main character (Charlotte Alton) that did not fit the usual mould. Hearing her readers’ comments that her character should have been a man or given some sort of mental illness to make her more palatable has made Giltrow incredibly glad that she wrote the character that she wanted to write.

Dan Hollloway began his talk by reading a 1 star review of his book on Goodreads that described The Company of Fellows as ‘by far the most depraved and perverse thing I have _ever_ read’. Holloway called this an accidental 5 star review. To Holloway, it is important to write passages that he hopes people find uncomfortable, so that readers can confront, or even inhabit, aspects of themselves they wouldn’t normally acknowledge. He discussed freedom in terms of responsibility too, and the conflict he felt with certain scenes between his responsibility to a character (the need not to flinch, or look away), and his responsibility to any vulnerable readers (the need to not glamourize suicide for instance following guidelines set out by MIND and other charities).

Mick Herron spoke the least of all four authors initially, explaining that he has ‘difficulty talking about what I write’, but his extract from his next novel, Real Tigers, was a real hit with the audience, mixing pithy phrases (‘like most forms of corruptions, it started with men in suits’) with incongruous gruesome humour involving Fathers 4 Justice. In the discussions, Herron spoke eloquently about the need to stay true ‘to how you created [your characters] in the first place’, as well at his frustration at many endings in crime fiction (‘as if the last 10% was written in a different genre’).

The discussion between all four authors started off with a slightly strange Hilary Mantel-specific question from the audience. Fortunately, the writers managed to broaden its scope to discuss wilful use of anachronism in novels. Holloway suggested perhaps placing a false note early on in the novel so it’s out of way: ‘then you can get on with the story’. From then on the conversation covered various topics such as the role of commercial restraints on the creative process (‘self-publishing is the worst for that’ quipped Holloway), and whether you can infringe on your characters’ freedom. Giltrow compared the restrictions of crime writing to those of a sonnet: how you play within the boundaries is what’s important. Overall, this was a well-thought out evening of four clearly different crime writers finding new ways to make the genre their own.

Blackwell’s fiction week continues tonight with David Mitchell in conversation with Michael Prodger at the Sheldonian Theatre, Charlie Hill and Zoe Pilger tomorrow, Ali Smith on Friday and Deborah Harkness on Saturday. Full details here.