Mine by Holly Corfield Carr

-Reviewed by Harry Giles–

Finding ways to document live performance is a perennial problem for the performing arts: watching a video of a show is rarely enthralling, and photographs and scripts usually fail to capture the sense of intimate action. Often documentation is used purely for marketing purposes, missing the maxim that “How we talk about art work is the art work”. But documentation, if it’s treated as creating multiple artworks from the same set of ideas, holds huge potential.

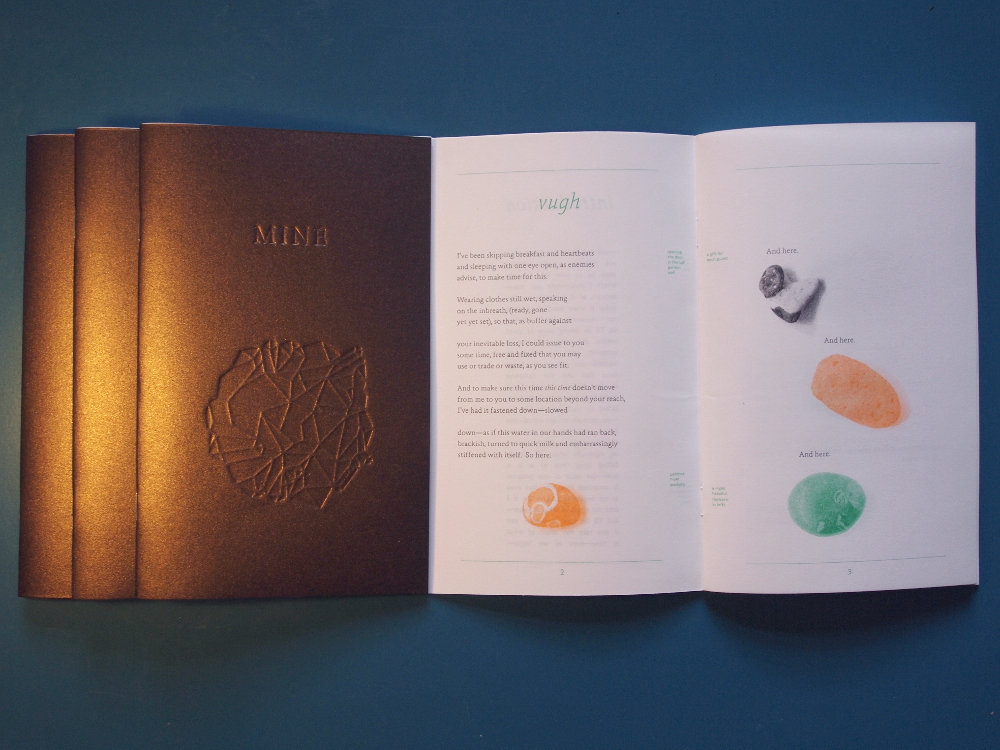

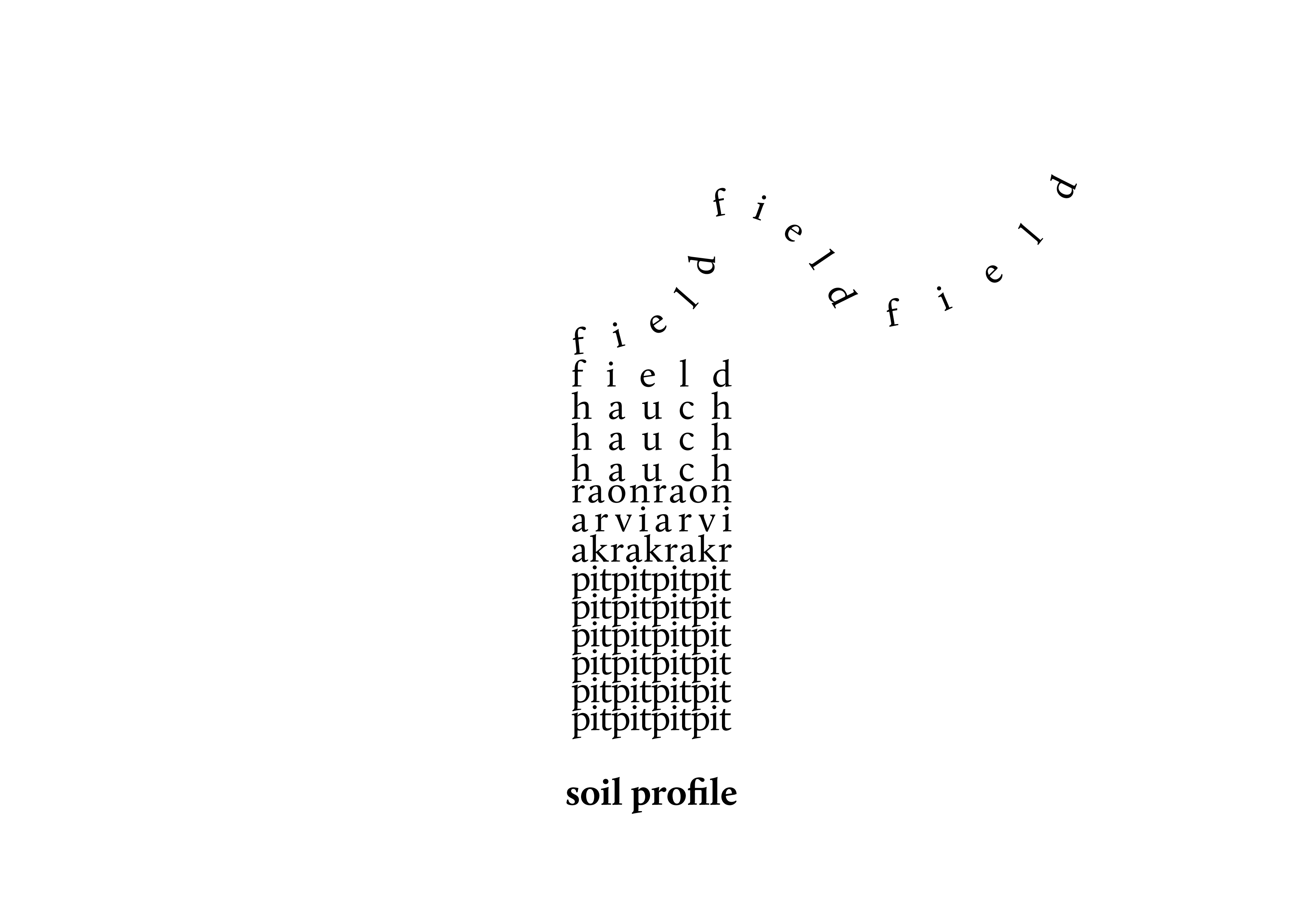

Holly Corfield Carr’s MINE is an intimate live performance and a poetry pamphlet. The performance was created for the Bristol Biennial 2014, and I didn’t see it; I only know about it from the traces it has left on the Biennal website and in my review copy of the pamphlet. The pamphlet renders the script of the performance – or what is presumably the script, or part of the script, or a version of the script – as a poetic sequence, with stage directions as monostitch marginalia and three-tone images representing props and interactions.

In this sense, the pamphlet is a documentation of the performance, but, if the pamphlet is formal poetry in a forever-fixed presentation, then the performance is also a documentation of the pamphlet. Any live performance only references its script; however accurately, it must add at whim coughs, disfluencies, phatic speech and so on. The stage directions for MINE also describe interactions – the performer and the audience exchanging pebbles as representations of time, and playing a basic card game – which can never go quite as smoothly as described. A performance is thus a kind of documentation of the idealised poetry represented in the pamphlet. Pamphlet and performance are shadows of each other, and each exists only in reference to the other: the performance of a poem depends on the idea of a complete and written version of the poem, and the published poems only make sense as part of an imagined performance.

MINE as a publication is very beautiful, and summons that imagined performance far better than any photographs could. Illustrations and stage directions take up as much space as the poems themselves, and are a counterweight to the dense and often abstract verse. Printed delicately in three colours on good thick stock, with an embossed cover and an (I think) hand-pasted photograph at the close, it has an impressive materiality – and its physical presence is necessary to its ideas.

The poems return repeatedly to the idea of objects as a kind of fossilised time that we exchange with or gift to each other. They discuss the performance’s site of Goldney Grotto not just as a physical place, but as a trace of history left in time, recording the slave trade, prehistoric marine life, and flows of rock. The pamphlet is the performance’s physical trace, its pebble of time. But the precise nature of these traces and exchanges is never quite graspable, and language is slippery. Carr has a playful, alliterative tongue:

And here. Oxheart clam. Glossus humanus.

The shell looks just like a valentine. All loose ligament and

little hinged teeth and two parts put loosely together

so that the calcite lump at the ends of our tethers,

our nethers, our heavy-headed songs and lungs, our own dear

heart jumps in recognition […](from “glossus humanus”)

This is poetry grounded in the Anglo-American lyric tradition, but with much less restraint than is usually favoured – to its credit. I can imagine “our nethers” getting workshopped out in most contexts; it takes conviction to keep in a third rhyme so cheeky. The play is rich, but never uncontrolled, and relies on a degree of free-associating uncertainty, because, as the poet says, our bodies are arranged

as if, in suffocation (we will all lose the words for this,

we will all bury ourselves for this)

as if, in vindication (you can’t take this

where we’re going).Because even now, time is up.

The stone you hold is moving, is sand at your hand.(from “time’s up”)

MINE is deeply embedded in systems of public funding. The logos of five arts bodies are stamped on the final page of the pamphlet, and the artist’s biography tracks an Eric Gregory to Faber New Poets career trajectory. It’s remarkable, given this scale of backing, that something so small and neat has been made: the pamphlet has as much depth of texture and richness of theme as a fabled “full collection”, but is condensed, pressed and polished. On the other hand, it’s precisely such a constellation of funders that makes this kind of work possible: intimate performance is notoriously unviable based on ticket sales alone, if the performers are to be paid, and pamphlets tend to need to keep production costs and unite prices below the sophistication of MINE. The multiplicity, originality and lustre of this publication should be a challenge and an inspiration to traditional poetry publishers: poetry pamphlets offer a greater range of expressive possibilities than most book formats, but is there a market for them? Is there a way they can be less ephemeral, or at least that they can be marketed to wider audiences? Similarly, the production values of the pamphlet are a beacon to zinesters and indie publishers, though they may be inaccessible without funding support. Work like MINE deserves a larger audience and dedicated attention, so that more of us can follow the traces of tiny performances and great flows of stone.

Copies of MINE can be purchased at Spike Island and Arnolfini in Bristol. They can also be ordered directly from the author by emailing hccwriting at gmail dot com. The price is £5 including postage.