Drag City by Charlie Baylis

-Reviewed by Simon Turner-

I’m a long-term fan of Charlie Baylis’ poems, and it’s excellent to see a small selection of them gathered together in this reliably neat package by Broken Sleep Books. Drag City opens with a disarming poem, titled simply ‘hi…’, which sets the tone of the collection remarkably well:

now we’re friends, i’ll tell you about my buttercup

china, the dragon, the fire eater, my lemonade.

why are you standing at the traffic light?

the light is green – confused or worse –

let’s be friends.

There’s a lot going on in this poem, not the least of which is the deft way Baylis uses and abuses the old rhetorical trick of directly addressing the reader. When deployed by other writers, the device can prove to be a little too whimsical and cute. Baylis pushes proceedings towards the sinister alarmingly quickly (when did the reader and speaker become friends, exactly?) A sensation which only becomes more acute midway through Drag City by way of a disembodied fragment that reads, in its entirety, “now that we’re friends / let me show you all the ways i will hurt you”.

Nothing is stable in Baylisworld, and the poems throughout are marked by a kind of woozy sensuality, unfolding with the logic of a dream. Baylis is particularly good at arresting phrases and images that catch the eye and ear, but never allows themselves to harden into paraphrasable meanings. A few random examples:

“she

dives into the ice cream

clouds”

(from ‘lana del rey’)“like a snowflake eluding the cat’s eye”

(from ‘daisy miller’)“the moment her hair spilled into yellow flowers”

(from ‘a+ e’)“the sweep of evening sun

sets the bible belt’s purple

haze on fire”

(from ‘the waves at dawn’)

James Wright used to be very adept at this kind of thing, and Baylis’ tendency to alert his readers to his forebears suggests he’s writing from a similarly Surrealist-leaning tradition. The New York Schools (both first and second generation), in particular, are a recurrent touchstone. ‘revolutionary road’ name-drops Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, and Bernadette Mayer (with Allen Ginsberg thrown in for variety); whilst ‘IMPOSSIBLE!’ employs the opening of John Ashbery’s ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ as its launch-pad into flights of disjointed fancy:

Shave of Parmigiano, dropped-off in a blue truck

right click to the raven gathering water in its beak

the trout balancing in a light beam, cut together

first movement moving the waves the swan swims

up the heel of the cliffs we reach Assisi we reach

the gardens of Ferdinand we surface in New York where you

are measuring yourself against death

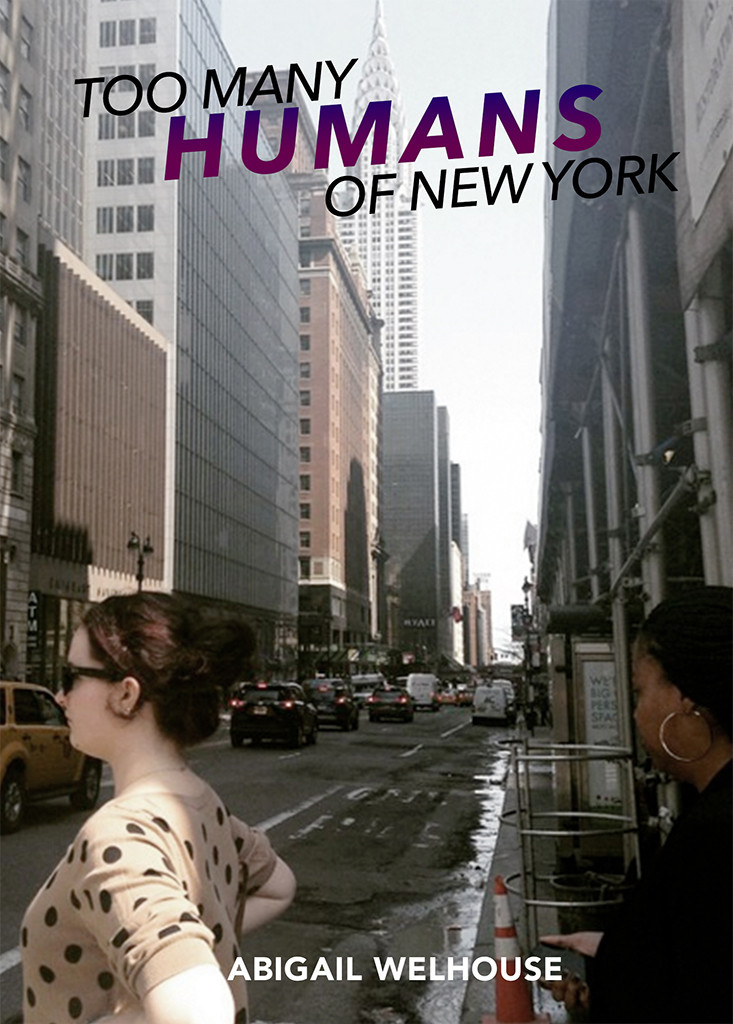

Without doubt, Baylis displays a more fractious and over-caffeinated technique than the bulk of Ashbery, but this still feels like a viable tribute to him. As with Ashbery, we never know what is coming next in a Baylis poem, they read almost like landscapes we’re discovering for the first time, perhaps in tandem with the speakers themselves. The disjointed technique of the poems – employing, I’d suspect, elements of collage and cut-up – becomes, then, less a matter of aping high modernist alienation than a necessary means of recording the ecstatic rush of sensory data that Baylis is responding to. It’s no coincidence that many of the poems in Drag City invoke or take as their setting the semi-mythical urban spaces of the US. Whether real or imagined – and I would argue that it’s irrelevant which – Los Angeles and New York perform a synecdochal role in Baylis’ work as shorthand stand-ins for the fractious, hyperactive delirium of just being alive.

Drag City reaches its peak in ‘charlie wave’, which takes the list poem to new and rhetorically hypertrophied heights. The poem is comprised of a series of disconnected statements, each prefaced by the word ANTI (the capitals are Baylis’, not mine), and which veer between childish invective (“ANTI your god-awful taste”), self-referential metatextuality (“ANTI you have stopped reading this poem”), and the grandiosely poetic (“ANTI everything that has been / ANTI everything that will follow”). ‘charlie wave’s’ relentless assault comes to a conclusion with the brief, gloriously narcissistic closing line “PRO charlie”, which, when I first read it, made me sit up and really pay attention. (I even considered saluting.) We can read ‘charlie wave’ as a punk remix of Edwin Morgan’s ‘A View of Things’, another excellent example of the art of anaphora, and I would argue that there’s more than a dash of Mayakovsky’s self-mythologizing folded into the mixture (Morgan, like Koch and O’Hara, was a confirmed Kovsky nut, so it’s not beyond the realms of probability). More importantly, it’s just a great poem: vivid and volatile.

Not all of the poems, however, are as successful or arresting as ‘charlie wave’. ‘from fifty shades of prufrock’, for example, is comparatively slight, although the incidental pleasure of imagining Eliot’s indecisive avatar wandering amid the wipe-clean interiors of E L James’ tawdry bestseller is probably worth the entry fee. I was also less convinced by both ‘a + e’ and ‘four tercets concerning my sister’, in spite of the latter including a world-class gag at Nick Clegg’s expense (we need more of these), as they felt more controlled and conventional as poems than many of the other examples in Drag City, and as such proved less successful vehicles for the Baylis brand of nervous energy.

Finally, Hiromi Suzuki’s illustrations should not pass without note, as they’re an excellent accompaniment to the poems. Just as Baylis’ writing hovers between dream and reality, so Suzuki’s pieces manage to navigate deftly between abstraction and physicality. There’s a tangible chewiness to these images that I liked a great deal, and they feel physically present in a manner that isn’t always the case with work that so totally eschews figuration.

In the final measure, Drag City is an excellent collection and, in spite of its title, in no way a drag. Baylis, much like the artists he invokes in ‘IMPOSSIBLE!’, is “attempt[ing] to do something unusual”, which is ultimately what poetry’s for.