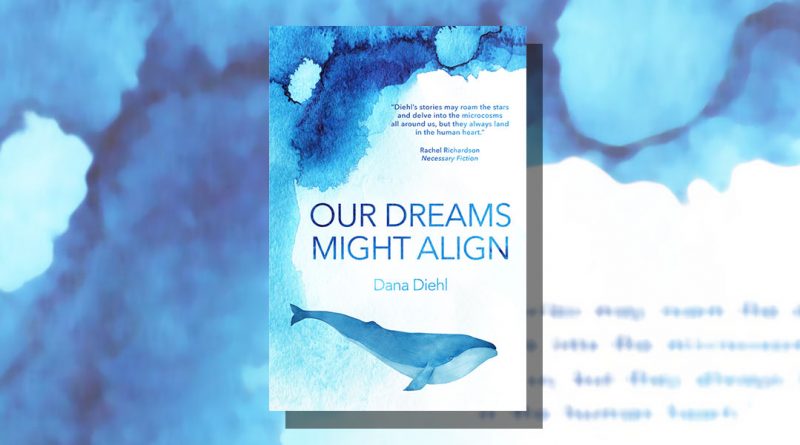

Our Dreams Might Align by Dena Diehl

-Reviewed by Mikiko Fukuda-

Dana Diehl’s short story collection, Our Dreams Might Align (Splice), is an homage to the loneliness we experience even in our most intimate relationships. Diehl’s characters find themselves on thresholds, confronted with their singularity and solitariness. The theme of lonesomeness is prevalent throughout every narrative and affects people and animals alike in spite of their desire to connect with other living beings.

‘Swallowed’ is a heart wrenching tale of two brothers who search for and are “swallowed by the loneliest whale in the world.” With overtones of Moby Dick and the biblical account of Jonah, Diehl’s narrative may also be inspired by a real-life whale’s song that was recorded by the US Navy in 1989. Like its real-life counterpart, the fictional whale’s song registers at fifty-two hertz, a pitch too high “to be understood by its brothers and sisters.” After two days of living inside the whale’s stomach and trying to yell to each other over the vibrations of the whale’s song, the brothers’ thoughts transform from the dual we to the singular I as each thinks, “I’m afraid I’ll die here, and my skeleton will traverse the seas forever in the stomach of a beast. I can still remember the briny scent of our father’s shoes when he returned from a sea journey.”

Yet it’s during this remarkable adventure that the brothers—perhaps simply because of their close proximity—rebuild their relationship: “Enclosed in the whale’s loneliness, we feel like brothers again. We call each other brother, but it’s the first time in years that it’s been true.” Sensing the whale is forlorn, together they attempt to communicate to the whale that they, too, are lonely—even in their brotherhood—admitting that even close kinship doesn’t prevent a feeling of hollowness.

Similarly, Danni the narrator in ‘Burn’ acknowledges, “What I wanted as a kid I still wanted—to be a double, to have my actions tied to another. But Lily and I had moved past a time when that could be us.” Danni’s discovery comes after two days of being cramped in the confines of the hotel room she shares with her sister, Lily.

Diehl’s stories about solitude in familial bonds also extend to parent-child relationships as is the case in ‘Animal Skin’, ‘Another Time’ and ‘The Mother’. In ‘The Mother’ we’re introduced to a woman who has given birth to forty-three children. In the moments before her death, her motivation for having so many offspring is revealed: “She never thought she would die. She thought she could cheat death by multiplying, by spreading her DNA over the earth.” Although twenty-four of her children are able to return home to her fifteen-room house to be with her, she realizes that “she’s surrounded by herself.”

The loneliness she feels seeing her reflection in the faces of her children is compounded when she likens a mother’s body to “a house full of rooms that are always being left.” The emptiness readers are left with is palpable.

While it can be natural to drift apart from family, it seems contradictory that we’d feel lonesome in our romantic relationships—especially new ones. But Diehl’s portrayals of the desolation we feel from loss while in a relationship is staggering. In ‘To Date a Time Traveler’, a couple in college are confronted with the unnamed boyfriend’s fantastical dreamscapes, dreamscapes which transport him farther back in time, distancing him away from his girlfriend. She recognises her boyfriend is trapped, obsessed with dreaming. In the same way, Ashton’s girlfriend in ‘We Know More’ recognises that her partner’s wondrous hallucinations are a side effect of a tumour that can’t be contained. Both women are dating men who are consumed by their own imaginations.

In addition to bearing witness to couples in budding relationships, we also become acquainted with the changes married couples undergo in ‘Astronauts’, ‘Swarm’, ‘A Place Without Floors’, ‘Closer’, ‘Once He Was a Man’ and ‘Going Mean’. Even though each marriage is at a different stage, Diehl captures how isolated and disconnected a person can feel from their spouse. Diehl’s characterization of couples asks us to consider the normality of feelings of detachment from a partner. We see the extreme disconnect between newlyweds, named “girl” and “boy”, in the story ‘Swarm’ after a canoe accident. The girl—concerned with saving herself—remembers her husband only as an afterthought:

“She paddled toward the bank, arms pebbling with goosebumps. She pulled herself up onto the reedy shore, gasped for breath.

Only then did she remember the boy.”

The girl briefly looks for her husband. Almost instantly her perception reverts to that of someone who is unattached:

“She was no longer a girl with a boy. She was a girl starting over. She was a girl back on top, the slope of her life tilting before her. Free to go to Thailand, to sell the ranch on the hill. So easily she could climb, dripping, out of the rapids that pulled him under.”

The ease with which the girl can imagine a future without the boy is unnerving for the reader. Yet it’s easy to understand: she was so distracted with the wedding that she forgot about the marriage to follow. At the end, we’re left wondering whether or not the girl will stay with the boy. The ambiguity at the end of ‘Swarm’ is similar to that in ‘Going Mean’, a story about Philip and his unnamed wife. After moving to Germany in an attempt to save their marriage, Philip comes “home [from work] with two baby Komodo dragons.” The wife hasn’t yet found a job and forms a bond with the dragons while Philip is at work during the day:

“I leaned back and turned until, like the Komodos, I was sprawled on my stomach across the tiled floor. I reached slowly, touched the dragon’s side. […] The dragon’s eyelids flickered. I could see my reflection in its black pupil. I expected it to twist, to bite me […] but instead it flicked its tongue. Nudged me with its scaly nose.

I inched away, my heart pounding. The dragons recognized something in me.”

Like the brothers who understand that they are lonely like the whale, the wife perceives a wildness that she shares with the Komodo dragons. Her companionship with the dragons is more honest than the companionship she shares with her husband.

As she lets the dragons outside one evening, she envisions their rewilding and is attuned to what they want: “They were dragons […] and they wanted better than comfort. They wanted wild.” As the three climb over the fence together, it’s unclear if they are all on the verge of escaping from captivity.

The characters in Dana Diehl’s collection of short stories hint that separating themselves from duality or plurality in their close relationships is freeing albeit difficult. Diehl’s exploration of lonesomeness is appropriate given our current global situation: as we enter lockdown, we may be a part of a collective or apart from them. Whatever your present situation, Our Dreams Might Align is a book I recommend getting cosy with as it reminds us that it’s okay to embrace—and even enjoy—being lonely.

Find out more about Our Dreams Might Align on the Splice website.

Reviewed by Mikiko Fukuda — Mikiko obtained her MA in English Language and Literature from The University of Victoria in Canada. She has worked as a language and literature instructor at post-secondary institutions in Canada, Japan, Kuwait and Oman. She worked as the Editorial Manager at a publishing firm in Shanghai. She currently works as a freelancer for Oxford University Press.

An avid reader, Mikiko runs a book club and enjoys writing poetry and short stories.

Instagram: @mikifoo82 | Website: https://thetravellingeditor.blogspot.com/