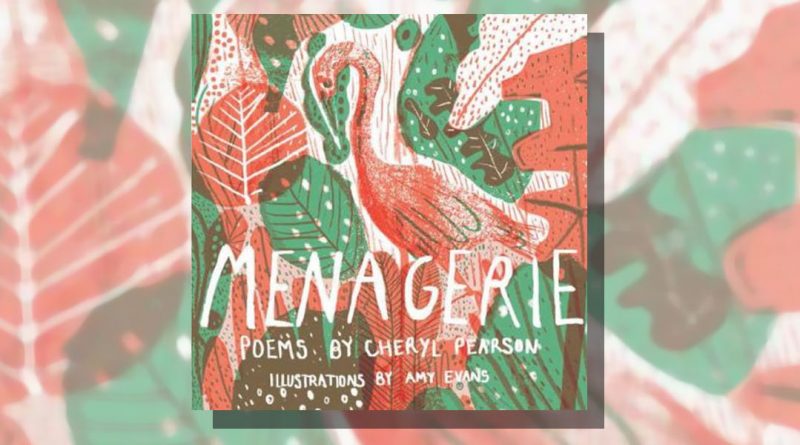

Menagerie by Cheryl Pearson

-Reviewed by Alice Allen-

The opening poem in Sheryl Pearson’s astonishing pamphlet of meditations on animals invites the reader to ‘Consider the Seahorse’ in its miniscule innocence and in distinct comparison to the four-legged equine kind. Seahorse language has:

no run, no season; his world has no corners. No apple

cores, or sugar cubes, but look: he rides the blue light

bareback. No bits or blinkers. No harnesses. No gates.

Throughout, Menagerie makes us consider not only living creatures and the universe whose evolutionary physics created them but also the workings of language and poetry itself.

Pearson has a real skill at capturing living movement. In the poem ‘Octopus Tank, Torbay Aquarium’, an octopus’s elaborate and cumbersome elegance is hauntingly recorded as she navigates the tank. A measured use of couplets and repetition in this poem slows the reader down to the pace of the trapped creature:

She flows away from the roof coming off –

the noise, the punch of light from the torch.

Unspools and re-ravels as we watch. First

fast. Then slow. A surge, and a gathering back.

A surge, and a gathering back. It lifts the hairs

on your arms and neck, makes a ballet of the tank.

Not all the creatures are trapped. Some are free like the Blue Mole, ‘Piped from the clench of his mother’s hind’ and his mother too who ‘fills the burrow/with the smell of light’. Most free of all is the hedgehog, conjured in a poem whose descriptive voice has become intentionally fused and muddled with animal and which charmingly condenses a hedgehog’s impulses and instincts into poetic language as rich and strange as leaf mould.

Pearson’s remarkable ability to capture the appearance and presence of living things is not merely decorative or spun for our amusement and pleasure (as was the purpose of the wild animals in the original menageries). Her figurative prowess draws our vision closely in, sharpening the lens, and results in a deepening empathy with the animals, birds and sea creatures represented in her poems, empathy with the aquarium octopus and the lobsters, who, ‘For lack of rock or wreck,/…climb each other, rubber banded/ for the restaurant tanks.’

Or the giraffe, euthanised at Copenhagen Zoo because he was deemed unsuitable for breeding, and who was publicly dissected, ‘Laid out flat like a flag, or hunter’s rug,/ a human peg at each streaming corner.’ A link between our mistreatment of animals and the implications it may have for human life is suggested in the image of the baby bird lying dead on the path in ‘Fledgling’ whose ‘featherless translucence’ reminds her of ‘the plucked birds hugged by supermarket/plastic, cleaned of clucks for the plate.’ Of the fallen fledgling the speaker asks:

…How can this bird, limp and broken,

speak to me of a blue dress, my first kiss?

The first time I fell, yes; the first time I flew.

The connection between human and animal life is one we disregard at our peril.

The moon and stars are a recurring presence in the poems, as is the idea of interconnectedness in the natural world, with allusions to particles forged in the furnaces of living stars being recycled and threaded throughout the universe. In ‘Kingfisher’, fish scales in the tree from the bird’s droppings sparkle in the moonlight. In ‘Gold In The Lion’, an arthritic lion is treated with injections of gold, ‘Like/ they’re topping him up/with the smelted metals/ he’s made of’. And the herd of reindeers in ‘Hardangervidda’, return to earth in death, having been struck by lightening:

The metal lick of light that kissed

the metal in them: particles, perhaps,

from the same original star, an inevitable return

to lips and teeth. So that this, the collapse, is not a death,

but only those two old lovers meeting –

Here you are. After all these years.’

The expression of this idea of interconnectivity is achieved by Pearson’s highly charged yet perfectly pitched use of metaphor and simile, in poems that are alive with the most striking figurative language. The kingfisher falls ‘like a rainbow wrapped/around a comet’. The blue mole moves ‘like a drill-bit rolled in suede’. The peacock’s colours are ‘every fruit and jewel condensed’. This is writing that makes you wish you had the poet’s eyes, and glad she has committed her vision to paper.

Pearson makes us marvel at the imagery inherent in language itself, our tendency to describe things by reference to what they are like, and this is especially evident when we talk about the natural world – hermit crab, sea horse, the constellations of the night sky. The poem ‘Hermit’ shows how this impulse to liken is often intensified in poetry by making comparisons that are uncanny and strange. The sight of crabs taking bizarre objects for their homes (‘A crab/ drags a light bulb through marram grass’) leads us on to consider how poetry works:

What is a poem? A teacher asked of her third graders.

A poem is an egg with a horse inside, answered a child.

Two things lifted from commonness. Rendered peculiar

in coming together.’

As you would expect from an Emma Press publication this pamphlet is pleasing to hold in your hands and beautiful to look at with exquisite risographs by Amy Evans skilfully portraying the creatures and their habitats. There is no illustration of the hedgehog; he definitely speaks for himself and I’ll give him the last words.

Milk on flat moon comes

at dusk. Goodsmell meat.Yes yes wings yes legs. Yes

fat silver, teeth. Trundle dimfor hunger. All dark I am. All

mouthmouth. Terror me to small.Fox-piss bigger. Hoot and whoosh-

lights. Roll, then. Hide the tender.